Detection of pseudorabies virus antibody in swine oral fluid

Differential approach for PRV detection used with serum samples could be adapted to oral fluid specimens for use in PRV control and elimination.

April 7, 2020

Pseudorabies virus has been pretty much off the radar since its eradication from U.S. commercial herds in 2004, but COVID-19 is teaching us (again) that the world is small and we are all connected. So a short reminder that PRV is still around may be useful.

Beginning in the 1960s, clinical losses from PRV were an increasing problem in commercial swine herds in Europe, the Americas and Southeast Asia. In the United States, annual losses to producers from PRV reached $21 million to $25 million (USD) (Miller et al., 1996). The greatest challenge for PRV control and elimination was identifying healthy carrier animals — animals in perfect health that, when stressed by other infections, gestation or farrowing, would shed virus to susceptible animals in the herd and cause outbreaks.

These silent or "latent" infections in carrier animals occurred because the virus was able to move into the central nervous system shortly after infection and persist in nervous tissue without producing any infectious viral particles. Because the virus does not replicate during latency, it cannot be detected by polymerase chain reaction or virus isolation in typical diagnostic specimens, e.g., serum, using routine diagnostic procedures (Mettenleiter et al., 2012).

The problem of detecting PRV-latently-infected animals was solved by scientific breakthroughs in our understanding of the molecular biology of the virus. A key discovery was that some of the glycoproteins produced by the virus are essential to its replication and others are not. For example, a glycoprotein called "gB" is conserved, stable and required for PRV replication, whereas, glycoprotein "gE" is associated with virulence, but not required for replication.

These simple facts led to the development of safe, highly effective "marker" vaccines that allowed for differentiating vaccinated from wild-type PRV-infected animals using specific antibody assays (DIVA). Marker vaccines were based on PRV strains that did not contain gE — the glycoprotein associated with virulence. In contrast, wild-type PRV contained both gE and gB proteins. Testing to determine pigs' status was done using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays that detected both gE and gB antibodies (screening ELISA) and ELISAs that only detected gE antibody. Any animal that tested (gE-/gB+) had been vaccinated; any animal that tested (gE+/gB+) had been infected with wild-type virus.

Testing serum samples for PRV serum antibody using the differential ELISA was the basis for the success of the U.S. PRV eradication program and PRV eradication in many other parts of the world. However, PRV continues to present a risk to U.S. swine producers because it remains endemic in feral swine populations in the United States, Europe, Asia and elsewhere in the Western Hemisphere (Muller et al., 2011). In the United States, PRV has occasionally been introduced into "transitional" herds via contact with feral swine, e.g., Minnesota (2002), Wisconsin (2007). Reflecting the industry's concerns, among the 46 pathogens on the Swine Health Information Center Swine Disease Matrix, PRV holds the No. 4 position (after foot-and-mouth disease virus, African swine fever and classical swine fever).

Given its continued relevance, improvements in PRV diagnostics, surveillance, control and elimination need to continue. In general, contemporary surveillance methods are moving toward aggregate specimens, e.g., oral fluids, processing fluids, environmental samples, to detect the presence of pathogens in commercial herds. Collecting blood samples from individual pigs is less sensitive and more expensive. Therefore, the objective of this study, funded by SHIC, was to evaluate the possibility of transferring the serum-based "marker technology" to oral fluid specimens.

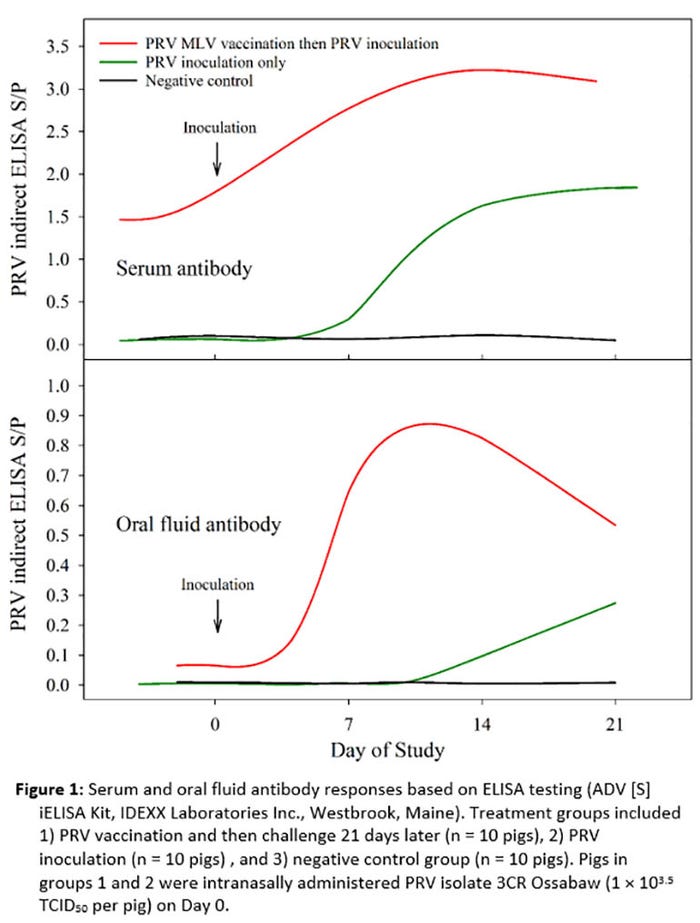

Groups of 12- to 16-week-old pigs were allocated to three groups (10 pigs per group): 1) PRV vaccination and then challenge ("Day 0 of the study") 21 days later, 2) PRV inoculation, and 3) negative control. PRV isolate 3CR Ossabaw (1 × 103.5 TCID50 per pig) was used in the experiment. Serum (n = 150) and oral fluid (n = 200) samples were tested for PRV antibody using a PRV whole virus indirect IgG ELISA (ADV [S] iELISA Kit, IDEXX Laboratories Inc., Westbrook, Maine); oral fluid samples were tested using a modified protocol.

As the results in Figure 1 show, PRV antibody response patterns in serum and oral fluid samples were similar. PRV antibody became detectable in serum and oral fluid about 14 days after inoculation in non-vaccinated pigs. A rapid and strong secondary boosting response was seen in challenged vaccinated pigs. In contrast, no serum or oral fluid antibodies were detected in the negative control group.

This work supports that concept that the differential approach for PRV detection previously used with serum samples could be adapted to oral fluid specimens for use in PRV control and elimination programs.

References

Mettenleiter, T.C., Ehlers, B., Müller, T., Yoon, K.-j., and Teifke, J.P. (2012). Herpesviruses. In J.J. Zimmerman, L. Karriker, A. Ramirez, K.J. Schwartz, and G.W. Stevenson (Eds.), (10 ed., pp. 421-446): Wiley-Blackwell.

Miller, G.Y., Tsai, J.S., and Forster, D.L. (1996). Benefit-cost analysis of the national pseudorabies virus eradication program. J Am Vet Med Assoc, 208(2), 208-213.

Muller, T., Hahn, E.C., Tottewitz, F., Kramer, M., Klupp, B. G., Mettenleiter, T.C., and Freuling, C. (2011). Pseudorabies virus in wild swine: a global perspective. Arch Virol, 156(10), 1691-1705.

Sources: Ting-Yu Cheng, Jeffrey Zimmerman and Luis Giménez-Lirola, who are solely responsible for the information provided, and wholly own the information. Informa Business Media and all its subsidiaries are not responsible for any of the content contained in this information asset.

You May Also Like